The award-winning author-illustrator Zeina Abirached was born in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War and, although she’s made numerous books as a cartoonist and illustrator, she keeps returning to the Civil War and the vanished Beirut that was razed and rebuilt after the war’s end, which is as much a character as it is a location in her work.

Alex Dueben talked to Abirached about this city, absent and present:

![za_1]()

Abirached’s two graphic novels which have been translated into English, A Game for Swallows, especially, and I Remember Beirut, which was published in the United States last year, show her trying to depict the city and to express a child’s vision of what happened during the war, not so much for the purposes of memoir but to reclaim a history that has been largely ignored or avoided by those constructing official histories. Her black and white artwork, like with Arabic calligraphy, is concerned with the interplay of vacuity and presence and she spoke recently about her work, memory, and researching the historical Beirut.

I Remember Beirut just came out, and it’s a very different book from A Game for Swallows, which is also about Beirut and growing up during the Civil War.

I didn’t plan to write I Remember Beirut. I was doing something at the time and some memories came back to me and it was very urgent to express them so I started to write small stories about the things I remembered. I was reading Georges Perec, he’s a famous French author, who wrote a book Je me souviens. It’s a bit like Joe Brainard’s I Remember. The book of Georges Perec is a list of many memories. Each sentence begins with “I remember” so it’s short sentences about his personal memories and the memories of his generation. At the end of the book he leaves three or four white pages with a note that if the readers want to write their own “I remember” they can do it on those white pages, so I started to write mine. I suddenly realized that I didn’t have enough space to write everything so I decided to write a book. There are many differences and many things in common. You already know some of the characters from A Game for Swallows. It’s about memories of my childhood and teenage years.

As Georges Perec did there are a lot of memories that are particular to my generation like Florence Griffith Joyner or RC Cola. My brother is younger and I think even his generation missed this. It’s very particular to my the people who are my age.

Like the sound of cassette tapes.

Yes! Every time I show the book to kids in schools I have to explain what is a cassette. [laughs]

![A panel from "I Remember Beirut."]()

A panel from “I Remember Beirut.” Courtesy of Abirached.

You end the book in 2006 during the Israeli invasion and being in France and hearing from your parents about the bombing. I wondered if that was the beginning of the book because it felt like that was where it started in a sense.

In this book I’m telling the story as if something is gone – like Beirut is gone – and in A Game for Swallows there is a lot of tenderness, as if I wanted to keep Beirut alive. In I Remember, even the title it’s as if it’s already past. I don’t know. In the French version the pages are not numbered. I wanted the reader to start the book anywhere. I’m not sure it started with the 2006 bombing. The first memory was the one about the first time we went to the Western side of Beirut. This is the first one I wrote. I was talking to a friend that day and I realized I remembered that the first time we went to West Beirut with my parents. I felt like I was in a foreign country and for the first two days I completely lost my mother tongues. I completely lost Arabic and French and I started to speak with everyone in English. I didn’t really speak English but I felt like I had to use a foreign language. I was 11, I think. It took me two days to realize that I was still in the same country–in the same city. I realized that I had to get to know the city after the war. We used to live in a very small place that was very protected and we couldn’t go to the other side. Once I was able to go to the other side I felt like I had to know everything about this other side.

I’m sure that your parents were trying to shield you from the war as much as they could while still keeping you safe. What has it been like for them to read your books?

[laughs] My mom was like “oh my god we did everything we could but it didn’t work. She remembers everything!” She was very upset. At first they were a bit surprised to see that there were so many things that I remembered, but I think it was also good for everyone to finally talk about it. Once I wrote this book we finally could talk about it as if it it was about our pasts. I think this was important for them–and for me of course–just to say, this happened and we can talk about it. It was difficult for me in A Game for Swallows to draw my parents and to make them talk. I don’t feel like they are the main characters. Do you feel that? I think it’s more about Beirut and everyday life and those people and it’s about this family, but we don’t really know who they are.

I think that’s true. There’s so much detail about the experience, but the book also gives the sense that it’s not unique. That something very similar is happening in almost every building on both sides of the city.

When I signed books in Beirut the first time, someone told me, we lived exactly the same, but on the other side. He was living in West Beirut. This was very important for me to see that we can connect with our memories. In Lebanon we really don’t talk about the Civil War. In school, the history books stop in the sixties.

You’re visiting Beirut right now, from your perspective, how has city changed in recent years?

A lot of things changed but a couple of months ago do you remember the graffiti in A Game for Swallows with the line from Florian [which gave the book its title]? This wall was torn down and for me it was very weird to come back and not to see this wall and the graffiti. Of course the city is changing and a lot of the old buildings are disappearing. I feel like we are losing–it’s too strong to say that–but it feels like we are losing our identity. Now the city is beautiful but I feel like it doesn’t belong to the people who are from here. There is an economic gap also – like everywhere – this is not special to Beirut. When I saw the wall of Florian has been destroyed I felt like the Beirut of my childhood and the Beirut I knew was completely gone. It’s not only about nostalgia, it’s also about what is replacing the things that were so particular to the city. I feel I’m too pessimistic.

![From Agatha de beyrouth, which Abirached drew live in Beirut in front of an audience. Courtesy of Abirached.]()

From Agatha de beyrouth, which Abirached drew live in Beirut in front of an audience. Courtesy of Abirached.

You’re seeing Beirut becoming more of a generic city.

There is also the war in Syria, which is very close to us. There are a lot of Syrian refugees as you know in Lebanon and Beirut so we also have a social crisis. It’s something you really feel when you’re here. You feel this new atmosphere. It’s contrasted with the new buildings and towers. We only have four hours of electricity in Beirut. Of course there a lot of generators, so we don’t even feel when there is no electricity. Some people are building this very luxurious, generic city you can find in Dubai or wherever. On the other side there is a social crisis and people who don’t have any place to go and refugees. It’s difficult to accept this. Right now I’m writing a story which takes place in Beirut in the sixties. I’m going back to the Beirut of my grandfathers before the war and I’m trying to have a thread between my childhood and the Beirut before I was born. I feel like I make books to try to understand what happened and what we still have.

You’ve made a number of books in France that haven’t been translated into English or come out in the United States. There’s your kids book Mouton, which is a great book about having curly hair. You seem to also make a lot of illustrations.

I need a lot of time to make comics so I also do illustrations for books or newspapers or magazines or posters for music festivals.

I illustrated a book with a French author Jacques Jouet. He wrote and I drew this book in three days in public in Beirut. It was an improvisation. We were sitting next to each other. He had his computer on which he began the story and I had a screen where I saw what he wrote and I had to illustrate this text live. It was like a performance. Eight hours per day for three days in public. It was great. Jacques is a member of the French literature school Oulipo with George Perec.

![From Agatha de beyrouth, which Abirached drew live in Beirut in front of an audience. Courtesy of Abirached.]()

From Agatha de beyrouth, which Abirached drew live in Beirut in front of an audience. Courtesy of Abirached.

How did that happen?

We were invited and they asked us to do that!

Sometimes I draw with musicians live in concert. It’s very interesting for me to go out of my studio and change my habits and draw in another way. When I work in my studio I’m alone and when I draw my books the style has a lot of detail. Live drawing with musicians or with Jacques was more instinctive drawing.

You mentioned that the book you’re making now is about Beirut in the sixties. What has it been like doing that and what’s the relationship between that and your other books?

It’s very different this time because it’s not autobiographical. It’s about the invention of a musical instrument in 1955 in Beirut. It’s my grandfather who invented it. It’s a piano. It’s a normal piano but when you play the piano it’s magical because it’s able to play music with quarter tones. I don’t know if you’re familiar with it but the construction of music in occidental music you have the space between each note is a tone or half a tone and in oriental music it’s a quarter tone. If you’re talking about the piano it’s as if there is not enough keys. He added a pedal which can switch all the strings inside the piano and so once you use this pedal you pass to oriental music and once you release the pedal it’s a normal piano. I really love this thing because it’s a bit of a bilingual instrument. I found it very interesting. It’s the story of this invention and how he went to Vienna to construct it and how he couldn’t really do it, actually, but I’m not going to tell the end of the book.

We still have the prototype he constructed in Vienna at my grandfather’s place. Because it’s in the fifties and sixties, it’s like a myth for us. I wonder if the Beirut of the sixties ever existed. [laughs] I mean it exists in our grandfathers’ memories but I feel like I need to know this era of Beirut. Right now I’m drawing downtown Beirut in the sixties so everything I’m drawing does not exist anymore. It’s very weird because of course I have a lot of pictures but it’s strange to draw the cinema for two days, with its very nice facade, and realize that I took two days to draw something that we don’t have a trace of anymore except for pictures and stories. That why I told you I wonder if it ever existed because it’s a bit like a myth and something that is too seems impossible now this place has existed.

Yes and that myth goes something like, Beirut was the Paris of the East, people from around the world studied at American University of Beirut and everyone got along and then all of a sudden there was this long, brutal civil war. There’s obviously something missing from that story.

Yes! My story stops in 1975 at the first day of the war. The main character in real life died in 1975 just before the war started, so he died thinking things would never change and things would always be like this. He died with the end of this era, and it’s a good way for me to get to know this period of time in Beirut.

Alex Dueben has written on books, comics and art for a number of publications including The Paris Review, The Believer, The Rumpus, The Comics Journal and The Daily Beast.

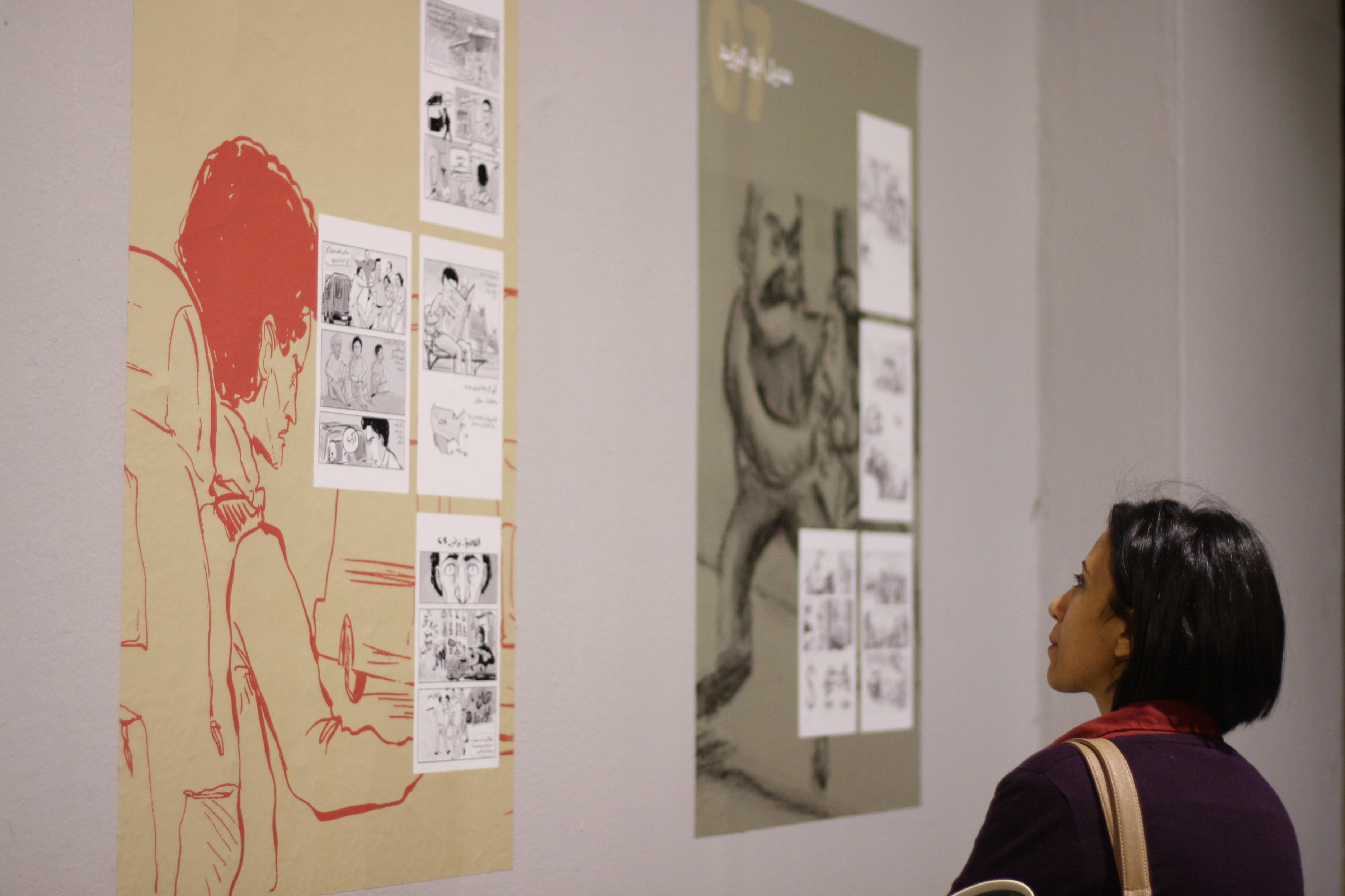

![]()

![]()

A City Neighboring Earth, (مدينة مجاورة الأرض) by Jorj Abu Mhayya, Dar Onboz, Lebanon. This won the prestigious 2012 International Comics Book Festival of Algeria (FIBDA) book award for a work in Arabic. See more here.

A City Neighboring Earth, (مدينة مجاورة الأرض) by Jorj Abu Mhayya, Dar Onboz, Lebanon. This won the prestigious 2012 International Comics Book Festival of Algeria (FIBDA) book award for a work in Arabic. See more here. Apartment in Bab El-Louk (في شقة باب اللوق) by Donia Maher, Ganzeer, and Ahmed Nady. This is a beautiful noir-esque work that’s as much poetry as prose, and Ganzeer asserts that this isn’t a graphic novel. He said in a previous interview, “I would never attempt to pass “The Apartment in Bab El-Louk” as a graphic novel or anything remotely close to it. Just because there are drawings, doesn’t make it a comic book or graphic novel. The sequentiality that would exist on a singular page of your typical graphic novel is nowhere to be seen in this particular book, save for the very last nine pages illustrated by Ahmad Nady. An entire story told in full-page splashes just isn’t a graphic novel. The narration is a little bit more designy, making the book more of a visual album of sorts. Or as you eloquently put it: ‘a fabulous noir poem.'”

Apartment in Bab El-Louk (في شقة باب اللوق) by Donia Maher, Ganzeer, and Ahmed Nady. This is a beautiful noir-esque work that’s as much poetry as prose, and Ganzeer asserts that this isn’t a graphic novel. He said in a previous interview, “I would never attempt to pass “The Apartment in Bab El-Louk” as a graphic novel or anything remotely close to it. Just because there are drawings, doesn’t make it a comic book or graphic novel. The sequentiality that would exist on a singular page of your typical graphic novel is nowhere to be seen in this particular book, save for the very last nine pages illustrated by Ahmad Nady. An entire story told in full-page splashes just isn’t a graphic novel. The narration is a little bit more designy, making the book more of a visual album of sorts. Or as you eloquently put it: ‘a fabulous noir poem.'” Jam and Yoghurt, (مربى و لبن), by Lena Merhej. One of the Samandal core, Merhej has a beautiful, charming style, here about her mother. I can’t believe I neglected to list this; thanks to Rania Hussein Amin.

Jam and Yoghurt, (مربى و لبن), by Lena Merhej. One of the Samandal core, Merhej has a beautiful, charming style, here about her mother. I can’t believe I neglected to list this; thanks to Rania Hussein Amin.  A Bit of Air (حبة هوا), by Walid Taher. All right, this isn’t a graphic novel at all, but a collection of cartoons, but one could call it more of a graphic poetry collection. Dar El Shorouk.

A Bit of Air (حبة هوا), by Walid Taher. All right, this isn’t a graphic novel at all, but a collection of cartoons, but one could call it more of a graphic poetry collection. Dar El Shorouk. Pass By Tomorrow (فوت علينا بكرة), by Sherif Adel, which is also available digitally, and has a frequently updated Facebook pace.

Pass By Tomorrow (فوت علينا بكرة), by Sherif Adel, which is also available digitally, and has a frequently updated Facebook pace. TokTok (http://www.toktokmag.com/). The premeire Egyptian graphic-novel magazine for adults.

TokTok (http://www.toktokmag.com/). The premeire Egyptian graphic-novel magazine for adults.

Ganzeer made the announcement on his “

Ganzeer made the announcement on his “ In both Paris and Berlin, AFP reports that the Syrian artist’s first book is being met with acclaim.

In both Paris and Berlin, AFP reports that the Syrian artist’s first book is being met with acclaim. The CORRECTIV fellowships are for a six-month residence in Berlin. Each fellow, according to the CORRECTIV website, “will receive free housing, roughly 10.000 Euro for expenses for living in Berlin for six months, and the flights to and from Berlin.”

The CORRECTIV fellowships are for a six-month residence in Berlin. Each fellow, according to the CORRECTIV website, “will receive free housing, roughly 10.000 Euro for expenses for living in Berlin for six months, and the flights to and from Berlin.”